Last month, AFTRS Research hosted award-winning director Sarah Ticho as part of the Visiting Scholars and Creative Practitioners’ program. Sarah generously invited AFTRS students and staff to explore the intricacies of her creative practice and the vast uses of immersive media, with a focus on her pioneering VR project, Soul Paint.

This immersive experience, voiced by Rosario Dawson, won the SXSW VR Competition Special Jury Award, the Games for Change’s Best Health & Wellness Award and the XR Special Mention at Kaohsiung Film Festival, pushing the boundaries of how immersive technology can affect health, research, and storytelling.

Sarah has a diverse background in arts, academia, healthcare, and technology, serving as a producer, curator, artist, and researcher. She has collaborated with organisations like the NHS, YouTube, and TEDx Sydney. Her academic work includes research with UNSW Australia and Stanford University. In 2018, she founded Hatsumi. Alongside her role with Hatsumi, she co-founder of the XR Health Alliance and continues to consult on other XR projects, and strategies for implementing immersive technology into health and wellbeing.

The conversation was moderated by AFTRS Head of Research, Dr Alejandra Canales and AFTRS Senior Lecturer, Dr Mark Ward. These are the key points from the discussion:

VR and Perception

Alejandra started by presenting the intersection between immersive media and health through the lens of the recently published – Embodiment, AI, and the Perception of the Real – A Report produced through MIT ODL x IDFA DocLab Research and Development Network, DocLab 2023 festival, published September 2024.

She quoted an excerpt:

“As creative media technologies continue to evolve, we are seeing expansion in the ways in which participants’ bodies are drawn into the produced experiences. Embodiment, on the one hand, is a persistent state of being human, and so any media experience is to some extent embodied. However, the affordances of immersive and interactive media technologies enable more explicit forms of embodiment, where movement and multi-sensory approaches can be incorporated into the progress of a work.”

Soul Paint transports users into a deeply interactive environment to explore self-expression and healing through body mapping, a tool often used to visualise emotional and physical experiences on the body. By merging VR technology with healthcare and storytelling, Sarah’s work displays how VR can transform therapeutic experiences, allowing users to see, feel, and interact with their internal landscapes.

Sarah started Soul Paint eight years ago, when in Sydney. The project gained life through immersive storytelling, aiming to transform perception, of ourselves, of each other and informing how media can be used as a therapeutic tool.

Her journey began in the UK, where her experiences with grief and loss after her father’s passing propelled her to explore the healthcare system and the role of art in bridging gaps in empathy and understanding. She explains how this experience was pivotal in her path:

“I became interested in health care and the idea that going to see a doctor is almost like a performance space. You have this very limited time to explain how you feel. So, I worked in the NHS briefly and then I started volunteering at this place called Fabrica in Brighton, where I’m from, and it was this amazing exhibition about grief.”

The exhibition provided a safe space and time to talk.

“And that was when I realised that art is a way of talking about things that are sometimes hard to make sense of. And particularly on a scale like that, that idea of being immersed in art fascinated me.”

Sarah developed an interest in storytelling and how it could impact audiences and perspectives on health care. She worked for a year on the Guiding Lights mentoring program and later decided to come to Sydney, seeking change.

“My first job here was working at TEDx Sydney, and there was a local technologist called Jordan Nguyen who gave this fascinating talk about how VR could be used to transform our identity and perception of self.”

While volunteering at the Sydney Film Festival, AFTRS Director of Partnerships & Development Mathieu Ravier (then SFF VR programmer) introduced Sarah to VR, further growing her interest in the medium.

“I tried pieces that were funny, uncomfortable, interactive, and passive. I was so inspired by the festival and the amazing installations at Carriage Works, and I thought – Alright, let’s do it.”

As Sarah continued learning about VR’s uses, she grew fascinated with its interaction with the human body. She saw how it could reduce pain in patients with severe burns and how it could be used in physiotherapy and rehabilitation, helping people reconnect with their bodies.

“I did a big research project a few years ago with the UK’s big arts and technology organisation about the spectrum of how VR can be used to improve wellbeing. We all know that being in nature can improve your wellbeing and reduce your anxiety. And so, there’s been incredible organisations like Marshmallow Laser Feast who’ve done these beautiful projects where you can go inside the tree or like Deep that allows you to breathe through these magical underwater worlds.”

Sarah explained how Deep, a meditative virtual reality game controlled by breathing, influenced her work.

“Deep is a breath-controlled virtual reality experience where you move through this magical underwater world controlled by deep belly breathing.”

“And this is something that fascinates me about VR. It’s not just about giving people controllers where you can have agency and interact in a very particular way. But how can we bring the whole body into the space.”

The piece originally used a belt to synchronise the diaphragm’s movement with the VR environment. Later, it was adapted to interpret hand movements based on tai chi, removing the need for extra hardware when interacting with it.

“As you can tell, it’s quite hypnotic and beautiful. And the way that the seaweed responds to your breath is incredible.”

As artists, scientists, game designers, and engineers develop VR’s potential, analysis starts to give us insights into how such tools can help reduce anxiety and how the learnings can be embodied to use in later situations even with no access to the VR experience that enabled the learning. These outcomes led Sarah to collaborate on policy development to enable access to VR tools through the health care system.

“In 2020, we wrote a report that lobbied the government to create a national strategy for immersive technology and health care, and we put together a lot of information about all the different ways that VR can be used to improve mental health. But also, how does this save money? How does this improve people’s wellbeing in a meaningful way?”

The government committed to investing in VR for mental health and created similar projects according to needs and results.

“And meanwhile, I’m still really passionate about how we make this available to the public as well because this is what is really happening in the NHS behind closed doors.”

The origins of Soul Paint

Sarah kept focused on the idea of the doctor’s office as a performance space and the fact that a patient has, on average, 11 seconds to explain how they feel before being interrupted. This led her to discover the use of body mapping as a visual tool to help connect with the body and express the embodiment of feelings and sensations. Sarah first came across such a tool via researcher Prof. Katherine Boydell from the Black Dog Institute, who facilitated a body mapping workshop at AGNSW.

“And I just loved it as this fascinating way of learning about people’s experiences. I walked away being like, I’ve got a lot of feelings I want to talk about, and I want them to come across as powerfully as I feel them inside.”

“It’s an incredible thing and it’s also used a lot in health care and able to be used as a tool to reduce trauma. And they found that drawing can reduce symptoms of PTSD by up to 80% if delivered after a traumatic incident.”

She became fascinated with the possibilities of exploring body mapping as a tool for expression in the health care setting, in a three-dimensional environment, including time as part of the exploration.

“How did the environment that you’re in transform that experience? How could you paint spatially? But also, instead of just drawing on a flat body, how can you draw on the skin or inside the body or outside the body? How can you create a narrative around it and create this form of embodied interaction? And, what can we learn from the artworks that people are creating?”

With Soul Paint the audience can paint emotions onto virtual body avatars, helping visualise and articulate feelings that are often challenging to describe. Sarah continued developing the tool, brushes, and functionalities, but it took a while until she leapt from drawing expressions of feelings to building narratives that gave the users some agency.

By allowing participants to engage with their emotions in a 3D virtual world, Soul Paint introduces a new form of storytelling that encourages users to narrate their experiences through colours, textures, and movement, then interact and even dance with their creations. She explains how it all came together:

“We asked the question: what if you could dance with your sadness? How can we take this idea of thinking about embodied experience and use VR’s affordances to push this further?”

She started learning more about dance’s applications for well-being and its impact on self-connection and understanding of emotions, boosting self-esteem. The Soul Paint team grew and applied for development funding in the Netherlands.

“We got funding from the Netherlands Film Fund to make a prototype, which we showed an interactive children’s Festival called Cinekid.”

“The kids loved it, and actually, it was like kids coming back and literally dragging their parents and being like ‘Mom, I want to show you what I drew’. Because, when I feel sad, it looks like this. And it was amazing seeing how those conversations really unfolded with people.”

Soul Paint continued to be developed considering messaging and experience, accessibility and safety, and implementation in physical settings. Because the interface differs from a cinema, and because the audience is still familiarising with such environments, it became important to consider how to onboard people and speak about the experience afterwards.

“How can we create new forms of connection in the community? What can we learn about this as well? What are the different ways that the people represent their embodied experience? How do things like language and culture inform how we talk about it? And within that as well, we also thought about, where does this go in the future?”

Soul Paint and the public

When completing the project and considering these questions, the team submitted Soul Paint to SXSW. Sarah explains how the public experienced the project.

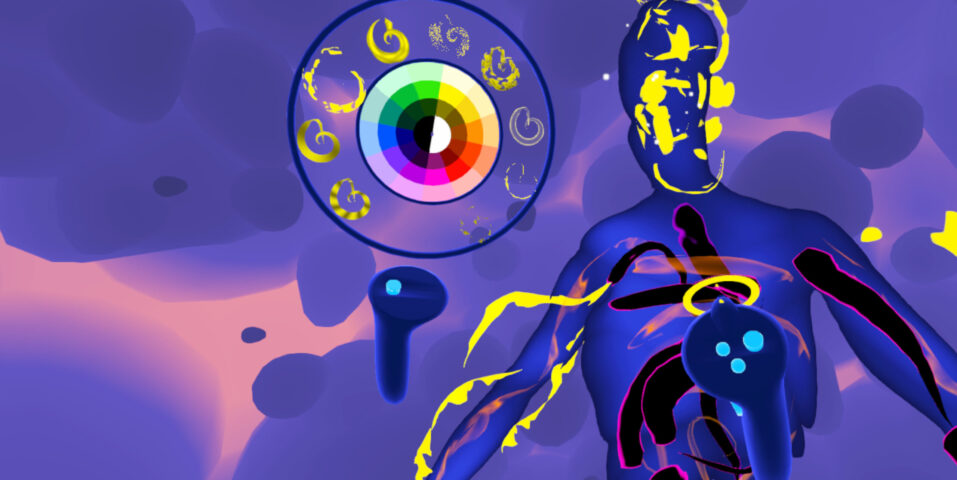

“When you begin the piece, you put on your headset and land in the entrance space – an otherworldly place where you are surrounded by a cloud like cocoon. When you’re ready to begin, you can touch this little cloud and then you meet your guide, voiced by Rosario Dawson. She introduces you to this world of feeling. She talks about how embodied a language already is. The butterflies dance in our stomachs, our spines tingle, and she starts to introduce you to the tools in the piece as well. It’s extremely interactive, offering you a palette, brush and microphone – so it takes a moment to familiarise yourself with the interaction.”

Soul Paint Installation

The user is introduced to the brush sets, different colours, and textures and receives an invitation to breathe slowly and deeply, reflected in a mirror where the user’s avatar is being traced, embodying the reflection.

“We landed on this ethereal, smokey avatar that is not meant to represent your body but give the impression of a body.”

“And then you’re invited to draw either how you feel today, a memory that you would like to explore. We intentionally made it quite open. We wanted people to bring their own stories and what felt important to them. Audiences can draw in the body, on the surface or even outside the body to create a life size representation of their embodied experience. After completing their drawing, they’re invited to describe what their drawing means to them before stepping back in and re-embodying their drawing. So, you’re seeing yourself in the mirror, and you get to move and dance with it, your avatar and its drawings become reactive to your movement.”

In this moment, the representation shakes off the symbols, colours, and textures, simultaneously with an invitation to explore the surrounding world and other people’s artworks (for those who consented to do so).

“We’ve shared the experience nearly two thousand times now, and it’s been amazing seeing the conversations that happened afterwards and the other people that have talked to me about their experiences of grief and loss as well.”

The project was awarded the Special Jury Award at the SXSW, and the team continues to develop and improve its interface to reach new audiences through different mediums including community settings, like performance, public installations and online.

“The big goal is how we can use this to have important conversations with the public about things that are hard to talk about.”

“So, the dream [among various digital distribution options] is to take all these artworks and make a physical terracotta army of embodied stories as a way of talking about all forms of lived experience.”

Stories are used to communicate and help us understand each other, exploring our own depth. The development of different media types enables us to connect, inspire empathy, and facilitate self-reflection.

“Because when you think about it, the arts have always been about health. The first artefacts that we found were fertility figures. There has always been this relationship between the things we create and how that relates to our stories, lives, and bodies. And that is where the arts and health movement show that this is not just a nice thing to have. It is integral to our lives and how we create purpose and meaning and connect to each other.”

Immersive media brings possibilities to the forefront because of the live interaction that enables the expression of various individuals through a particular lens, embodying the living experience of many into a communal way of expression.

For more on Sarah’s work, visit Soul Paint and Hatsumi, and stay tuned for more inspiring discussions from AFTRS Research. Thank you to Sarah for being so generous with your time and knowledge, to Alejandra and Mark for hosting the event in such an insightful way.