Throughout his career as a documentary filmmaker, Jolyon Hoff has shared the stories of Afghan refugees in Indonesia in The Staging Post, investigated the mystery surrounding a 1970s surfing legend in Searching for Michael Peterson, explored Australia’s iconic surfing culture in That Was Then, This Is Now, dove into private and government collections to form the extensive The Surf Film Archive and supported the establishment of refugee lead learning centres. In this chat with AFTRS’ Alumni Program Manager Christine Kirkwood, the award-winning AFTRS alum discusses his projects, and the importance—and challenges—of telling these stories.

CHRISTINE KIRKWOOD: Tell us about The Surf Film Archive, its beginnings, and how it’s going?

JOLYON HOFF: About fifteen years ago I was making my AFTRS graduate film Searching for Michael Peterson. As I was looking for footage of the famously enigmatic and mysterious 1970s cult-hero Australian surfer, I saw all these other film rushes lying around in garages and cupboards of the filmmakers. I always wondered what special and historical moments were on those dusty film reels.

Last year I started making a film about the influence of surfing on Australian youth culture. I decided to rescan the footage to use in the film and, with the pandemic and a few other factors, it turned into The Surf Film Archive. We are having so much fun. The footage is remarkable, much of it never-before-seen and lots of footage which is the first time any of those remote places were filmed, for example, Margaret River and other remote surf breaks around Western Australia and Indonesia.

The surfing is one thing, but the real gold is the cultural footage – the sleepy old coastal towns before they became what they are now, the cars, clothes, shops and people. The surf filmmakers were part of the youth culture movement and they made the effort to take their cameras where no one else was filming. The material is culturally historic and significant.

All the footage is scanned at 4K with our partners, Billy Wychgel and Gabrielle Joosten at Elements Post, and then it’s put on the website where everyone can watch for free. In time we hope we can deposit the material with a cultural institution so the material can get looked after for future generations.

CK: The Staging Post was released in 2017 and told the story of refugees seeking asylum in Indonesia. How did making the documentary change your life?

JH: The Staging Post grew out of a simple idea. I was living in Jakarta when Australia ‘stopped the boats’ and I realised I had never met a refugee. I drove up the hill where I heard they lived, took a random left turn, around a couple of bends, and then the Indonesian driver pointed “There, there’s a refugee”. I got out of the car and said hi.

That was Hassan, his English was not strong, so he introduced me to his cousin Rizwana, who found out I was a filmmaker and said I must meet her brother Muzafar Ali who was a photographer. Muzafar and I, and 17-year-old refugee Khadim Dai instantly became friends and started making short films together. When they decided to do something for their community they started the first refugee-led school in Indonesia and that process formed the narrative arc of The Staging Post.

That was ten years ago and it’s hard to measure the ways it’s changed my life. I now have hundreds of refugee friends! Muzafar and I started a charity and support five different refugee-led schools, which represents over a thousand refugees getting education. The idea that refugees need to be part of the solution in the refugee crisis is an idea that is slowly taking hold internationally.

CK: What is at the crux of a story that makes it worth telling?

JH: If a story is told authentically, it’s worth telling. I’m not a great communicator so I’m trying to express my ideas and share what I see around me. I’m always trying to capture and share emotion. I’ve spent much of the last fifteen years living in developing countries – West Africa, Indonesia, and Nepal. Through those experiences, I’ve learnt so much and made many friends. I have decided my job (for the rest of my working life) is to tell stories that bring these two worlds closer together. To make films that put both us (and them) in the same frame.

CK: As you said, you’ve travelled extensively around the globe and lived in countries including Nigeria and Indonesia. Do you think documentary makers have a global responsibility in shining the spotlight on issues of importance?

JH: We all have to care for and value our stories, without them we don’t exist. There are issues at the centre of my films, the story is the most important thing. Or ‘Story is King’ as the late great Billy Marshall-Stoneking would tell us.

CK: You’re working on a feature documentary called Watandar, My Countryman, which is inspired by the 160th anniversary of Afghan cameleers in South Australia. At the centre of the film is the journey of photographer and human rights activist Muzafar Ali, who featured in The Staging Post. What led you to create this work?

JH: Muzafar was stunned to find out that Afghans had been here for so long and started a photography project to photograph the cameleer descendants. He thought their experience in Australia might provide insights for his own children.

It turned out that many cameleers married Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous women and therefore their descendants are a mix of Indigenous, colonial and immigrant blood. But the important thing is that they have the one joint history! It’s a story that I think all of Australia can learn something from.

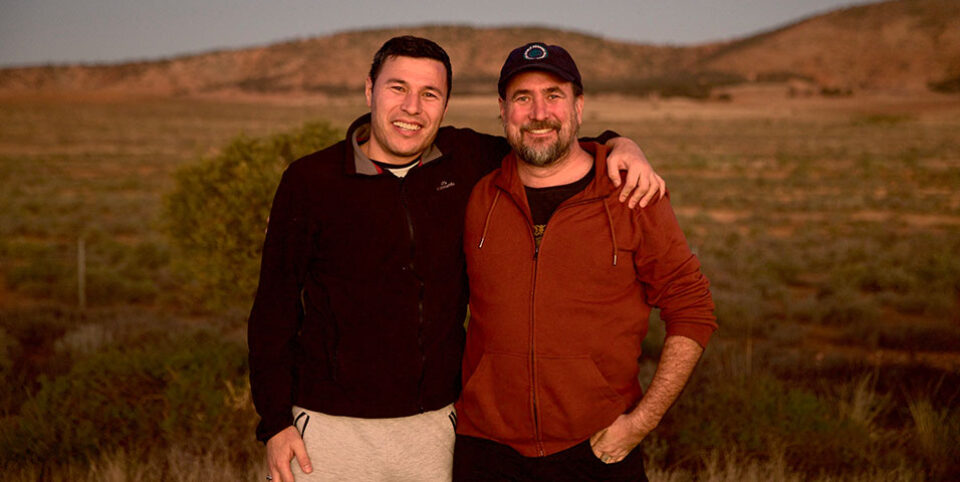

In 2022 Australia is re-imagining its mythology, and efforts are being made to acknowledge and value a broader range of contributions. The Afghan cameleer descendants featured in Watandar, My Countryman are Indigenous, colonial and immigrants at the same time. When Muzafar decided to photograph the descendants in an attempt to understand his own new Afghan-Australian identity, we started filming. His experience as a former Afghan-Hazara refugee, along with his wisdom and charisma, presented a rare opportunity to re-examine Australia’s colonial history. I’m excited to share this story and I know, through our previous experience with The Staging Post, that Muzafar’s charisma and his ability to engage in complicated ideas will connect powerfully with Australian audiences.

CK: Is it true that we can expect to see the documentary premiere at Adelaide Film Festival?

JH: Yes, in October this year. Mat Kesting was the first to get right behind the film and we are very grateful and excited to be screening it there for the first time. Now to get the film edited in time!

CK: Searching For Michael Peterson, your feature documentary about the Australian surf icon of the same name, screened at many festivals and was nominated for multiple awards. What gave you the hunger to set out on your mission to find the elusive former star?

JH: I had recently welcomed my first child and was thinking about how I wanted him to grow up, and what kinds of heroes I wanted him to have. Michael Peterson or MP is the ultimate hero for most Australian surfers. Tall, good-looking and enigmatic. He took more drugs, surfed better than anyone else and got all the girls. I was fascinated by the myth. Why were we all so intoxicated by this kind of character? It turned out that Michael had schizophrenia, which meant he disappeared from the surf scene when he was young, and this was why he behaved so strangely. He wasn’t able to manage in the spotlight.

CK: Do you have any pearls of wisdom for early career documentary makers?

JH: It’s easier to get the money to tell a story someone else wants to tell, but the challenge is to get funding to tell the story you want to tell. Make sure you don’t underestimate its value, and don’t underestimate the size of the challenge to get it made. You are up against everyone else and they all have more resources than you – from Rupert Murdoch to Rugby League, Sony to Disney. If you do create something, small or big, it’s an achievement and you should be proud. Once you recover, go and do it again.

CK: What’s coming up for you?

JH: As soon as we finish Watandar, My Countryman, we will be completing Australian surf documentary You Should’ve Been Here Yesterday.

We are also developing a comedy feature about Eric the Eel. Eric was the ‘Cool Runnings’ story of the 2000 Sydney Olympics. From Equatorial Guinea, he became an unlikely hero, for swimming the slowest but greatest Olympic swimming race ever.

We’ve also just optioned a book called Linden Girl. We discovered the story while making Watandar, it’s about a love affair between an Indigenous girl and an Afghan cameleer in Western Australia in the 1920s. It’s an update on the Rabbit Proof Fence story. It even has the same antagonist, A.O Neville. What a piece of work he was!