Last month, we were delighted to have AFTRS alumnus and multi-hyphenate talented writer, director, cinematographer, editor, composer Ivan Sen return to AFTRS for a special screening of his latest feature Limbo (2023) and a live Q&A in the main theatre. Ivan shared a breakdown of his ‘script to screen’ process grounded on an inspiring source of personal wisdom and experience on filmmaking.

Often recognised by his approach to filmmaking as an auter, Ivan is most known for creating the world of Mystery Road, which spawned a film sequel, Goldstone, and a TV series whose directors included other incredible AFTRS alumni Rachel Perkins and Warwick Thornton, with narratives centred on crime in desert locations. Limbo is a thrilling noir feature set in the outback with Travis Hurley (Simon Baker) playing an emotionally drained detective tasked with reviewing a 20-year-old case involving a young girl and the damaged family left behind.

David Balfour (AFTRS Director of Teaching and Learning) presented the Q&A in conversation with Ivan and the students and alumni in the audience. Here are the highlights of the conversation.

PLACE INFORMS STORY – SETTING THE WORLD AND PRESENTING CHARACTER

The first scene to be presented in the session was the opening scene of Limbo, with Ivan breaking down the essential elements to setup the tone and mood of the narrative.

He explains the importance of location and how the physicality of the space informs the story and the creative decisions, truly grounding the cinematic experience.

Ivan: “The script is untouched. So, I just wanted to show you how the script has gone through the image. And I was just saying before the process, that I kind of have developed, especially with this film… I kind of start from the screen to script and then back to the screen in a way where I actually work out visually from a concept point of view what I’m going to make by going to the locations and writing to the location and the identity of that location is what informs the story.”

The process becomes a circular writing process, where the location informs the image and thus influences the shaping of the script right up until shooting.

Ivan:

“This is my number one thing because I think, as an artist, if I don’t do that, I’m just making stuff up. And that’s not why I do what I do. I’m here on this planet and I’m actually trying to show my interpretation of what I see around me.”

Limbo’s main location is Cooper Pedy, a South Australian opal-mining town where citizens have created underground housing to escape the blistering heat. And the landscape does take priority on presenting us the story on screen.

The world is setup visually in its own time and with minimal editing, allowing action to flow through time and space until Travis is introduced driving to his hiding underground. Ivan takes us through the script as the scene plays out in the screen.

Ivan: “There is small town, but we didn’t really shoot this town. We just kind of ended up at the hotel to make things go a bit quicker. Just there a whole section like cut out [of the script] where he gets out of the car and has a cigarette by the Limbo sign. I felt like during the shoot that was going to slow down too much, to get him having a cigarette. And also pull away from the fact that he’s going to shoot up [drugs] shortly and that should be the focus of his fix.”

Ivan explains how he decided to focus closely on the main character in the first interior scene to show him changing his emotional and physical state and how the large format cinematography capabilities available today helped shape the scene.

Ivan: “It allows this kind of shot to work much better [the scene is shot in a confined space]. Allows you to be closer to your character, to feel them. But you’re still taking in that environment with the wider imagery. I mean, you had a sense of that before on anamorphic, but when you go large format, you can get closer and wider as well. Not that this was anamorphic, this is a spherical lense.”

The scene in the underground hotel room introducing Travis [main character] was shot in one day.

Ivan: “The whole hotel scene, all of this hotel room was shot in one day, which is absolutely nuts. Even for me, everything in that room was in one day, as well as the hallway stuff, which is with Natasha Wanganeen (playing Emma) and the other two guys who knock on the door. All of that was in one day with 4 minutes of overtime.”

The hotel is constructed based on various underground locations and filmed and edited to feel as part of the same space. This construct was built early on during pre-production through photography and scripting.

Ivan: “It’s about four hotels stuck together. The exterior is my underground apartment. And the bedroom is a backpacker’s kind of a downscale place and some of the corridors belong to several other hotels. The toaster at the breakfast area is separate from the corridor. Yes, it’s a combination of things. Building and constructing the whole visual thing is something that happened a long time before we got out there. I knew exactly where we were going to be. And it’s putting it all together.”

Ivan:

“As far as storyboards, I don’t storyboard, I go out and I just shoot the crap out of the location with my phone.”

When Travis is driving through the exterior locations, Ivan allows the landscape to dominate the frame before presenting the characters and Travis interactions.

Ivan: “He was at Charlie’s property, gets out of the car, there’s the caravan and the way he meets the people. I just had this thing in my head of just being very wide to begin with and allowing the landscape to be dominant, as it is dominant out there. Which is kind of that whole thing of the landscape or the location being the source of how I tell the story. And then we get closer to the characters as a scene progresses. And that’s how I kind of introduced all of the characters as Travis can connect with the characters to do his job.”

During the first dialogue scene, Ivan explains how the lines remained tight close to the script, and how the performance and editing can add weight to silence and pauses, allowing the audience to read into the situation.

Ivan:

“So you see that these words can be…. Charlie stares back at him and can be anything. But it’s your job as a director to make sure that that has a weight. These moments or these key moments have weight, which aren’t obvious on the page. So, they just do the look. And this is this technique again of the landscape revealing the characters and then we’re going in closer. So, you can see where the looks are. These are actually important moments.”

Ivan further explains the fine balance required to maintain the mood and tone of the film while keeping the audience engaged in the drama.

Ivan: “You have to be careful of being too contrived in that sense where it’s actually distracting to do something else [referring to camera angles and framing]. But pulling the audience out of that interaction of lenses, because I have learned that it might just feel like I used up to that point [referring to a wide shot]. We’ll cut in and we’ll go and do this, but it actually pulls you out of the drama. So, it’s all about keeping people in the drama in the end.”

David [Balfour] asked Ivan about the decision to go black and white, considering the importance of landscape and how the Australian outback has been historically represented and recognised by its shades of ochre colours and visually striking red dirt.

Ivan: “At this point in my mind, the film was black and white. But when I first wrote that sequence, it was colour. And I went on a bit of a journey going from 35-millimetre film as a possibility in colour and then ending on the black and white. And I actually kept it pretty quiet – the black and white thing – from everyone. I didn’t tell my producers about it, so they didn’t have to tell the ABC [Australian Broadcasting Corporation] about it.

Ivan:

“So, I remember the first morning [of production] my camera says: “Hey man, this morning we just wound up all the colour out of the camera.” And I said, put it back, put it back just in case, you know. I don’t think the ABC had played black and white film for a long time.”

When considering his creative decisions Ivan often refers to feelings as important clues to honour and trust.

Ivan: “It just felt right in the end. I mean, there’s a lot of reasons. You’ll see I even took a lot of colour film stills out there and when it became obvious that it was going to be too difficult to shoot film in Australia like it is now, I just thought, okay, I’ll go black and white. Because it feels right, it’s like these people are living in a memory that suits the tonality of Cooper Pedy, which is very rare in Australia, to have such a white base to work with on the ground and then building in the tonality or the design elements. You have a very good base to start with and it just felt right in the end.”

When opening questions to the audience, one of the attendees asked Ivan about the inspiration for the narrative.

Ivan: “Has a lot to do with my family and we’ve had a couple of murdered women in our own and now extended family. And I also know of Indigenous friends as well and their families. And I just know it’s something that touches a lot of Indigenous families. And this is a country that has a big issue with how it connects with not only Indigenous Australia but crimes against Indigenous people and how that kind of washes down through the whole justice system and is a representation of us as a nation. What we are drawn towards in the media and not drawn towards. And so, that in combination with this location kind of merged together.”

LESS WORDS AND MORE MEANING – STRENGHTENING THE SCRIPT TO ITS CORE

The second dive into the script-to-screen process focused on dialogue, exploring the importance of keeping words and explanations to a minimum and allowing the film to flow through action. Ivan takes us through the lines of dialogue that did not make the cut.

Ivan: “I just said Rob [Rob Collins plays Charlie], I’m just going to cut all this crap. And he said “Really?” Yeah, it’s better without it. And then I’ll move Miss Charlotte to the caravan, and we just do it there. And he [Charlie] still has the crying and everything in the caravan. So, he lies down on the bed, and I’ve moved all that stuff out, I didn’t even shoot it. I just shot him there [caravan] as it is. And as I’m shooting the film, the next morning I’m cutting the dialog out and putting it into this. Just to show you how you stay alive, how I try to stay moving and alive, as a writer constantly adjusting the script. When you’re out there and trying to keep it as pure as and as lean as possible to tell the story and because the dialog affects how you cover things too.”

He further explains why he prefers to make these decisions early on the process instead of shooting for coverage and then editing out in post-production.

Ivan: “You can do this all in post, but you try to fix as much as you can while shooting. You’re leaning into that way… I go on feeling. There’s no point where you feel things as much as when you’re actually shooting the film, because that’s where you’re feeling it and that’s your big opportunity to really drive that film to what you want it to be.”

Ivan:

“I could just cut those lines out in post but you wouldn’t get that performance from him and the whole thing would feel different because he’s in a state where he can’t deliver those lines. And for me, that’s his most powerful performance in the whole film.”

Ivan: “When you make a film it’s always trying to pop out of what it should be, of what it’s trying to tell you. You’ve got to rein it in, and if you do it before post, it allows you to use all your resources to tell that part of the story correctly and truthfully instead of just trying to Band-Aid it later. So, you’ve got to do it in that moment where you have a chance to feel things like you can never feel them any other time.”

Ivan emphasises the importance of capturing genuine emotions in filmmaking. He believes filmmaking is a personal and intimate experience centred around feelings and values the sensitivity of the filmmaker both during the shoot and in the overall filmmaking process.

Ivan: “It’s about feeling and just allowing yourself to feel things and being sensitive to everything and not saying no to things. But in the end, it comes down to what you’re feeling. When I’m shooting the actor, and we do a take and then I sit, and I’ll say to them “I don’t like it when you’re going down there and doing that. And I’m not feeling it. I’m not feeling it, man. I can’t feel it. I need to feel it.” So, he will do something else. Then I’ll say, “Yeah, I’m feeling it.” When you film, it’s such a personal thing for me, an intimate thing. It’s all about feeling not only on the shoot but beforehand and after you’ve shot it.”

PUNCTUATING DESIGN – PRODUCTION DESIGN APPROACH

In Limbo, the weight of the screen holds on locations and characters and because of this curated approach the production design elements emerge as fundamental on punctuating the story without overtaking the main elements. Ivan explains how some props were utilised in various locations, and how tone and shape intertwined with light and darkness.

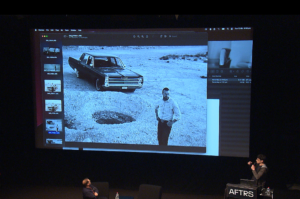

Ivan: “So the lamps… This lamp is in the whole film. It’s two of them and they’re just in the whole film. If you’ll see them, they’re the same lamp over and over. And the car, I mean the car was very important for me. It just had the right feeling, we did get it out from the Blue Mountains all the way there. And as soon as it came, I got my camera out and got to know how my camera and that car connected. That was really important for me to have that relationship begin very, very quickly. And then we’re going through a few days before we start locking down the costume and the glasses. And then I put him [Simon Baker] into the car and everything started to feel good. And then he just stood there like that.”

Ivan:

“I took the camera, and we went to some hills within the town. [Simon] had a chance to just be Travis. First time no one there except for me and him. Me with the camera and him. And I said, okay, just walk around, you know, Travis now, just be Travis. And so, he had a chance to kind of find Travis with no one around and feel.”

Ivan: ”An actor… sometimes I’ll say the clothes aren’t important, but I think they really are. So, once he got those clothes on, he started walking around those hills and he started to feel like Travis.”

Ivan presents stills of Simon on the landscape and explains how the large format sensor allows for exploring portraiture within the environment, bringing scale and ambience to enrich the story.

Ivan: “I think environmental portraiture is something I’ve always been into with stills. What I’m doing is like the environment informs the characters from the story.”

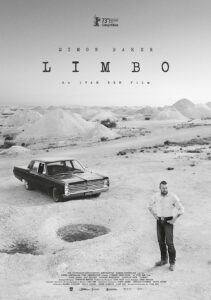

Ivan: “Before the script was written, there’s all kinds of things I do that’s nothing to do with sitting there writing. This is a very important part of the writing process. The car, some sense of the custom and the environment, you know, the holes there. And it’s not that different to the poster, you know.”

Ivan: “I just wanted to show you that still before we finished this, just to show you how you come up with the concept as a part of the writing process and screen to script to screen something beautiful.”

During pre-production Ivan visited the place several times to familiarise with the locations and the people living in the town.

Ivan: “I went out about four times and only for about three days at the most. It’s a kind of thing where I find that multiple small trips are much more useful than trying to stay there for a long time. You go for a few days, you meet people and then you go home. You think about it and you collect your thoughts. And then you go back again with fresh perspective and then you reconnect with the people and it’s like you’re best friends, you know, and they’ll do anything for you. And you find locations, you find actors and you write on a better location, and you really need to surrender yourself to it and to the people there and respect the people as well. That’s what I really try to do, get everyone involved and try to get money for everyone you talk to make sure they get money because it shows that you care about them.”

Ivan further explains his meticulous process of assessing a location, considering angles and visual elements that align with the story, underscoring the power of such locations in shaping and informing the narrative.

Ivan: “I go to a location and I’m trying to find out if it’s suitable. I’ll go through the whole scene, and I’ll look at all the angles and see if I can make it work. But the number one thing about location when I choose it is how far away it is from where we are. That’s the most important thing for me. First is, is proximity.”

Proximity of location facilitates the coordination required on production.

Ivan: “That’s basically it. It shows how powerful the locations are in informing the story. And this is the house. It belonged to one of the local miners. And all the angles you see here [Ivan is showing stills to the audience], the angles are actually in the film. And so, I’m knowing where I’m going to be pointing the camera as I’m checking the location and how suitable it’s going to be.”

Ivan prefers to work with lean production structures that allow him creative freedom and ends up taking on many of the creative roles himself, including cinematography, editing and composing. This hands-on approach and extraordinarily structured pre-production allowed for shooting the film in record time.

Ivan:

“We shot the film in 14 days, but that’s because I was doing weekend work on Sunday work when everyone else is enjoying their day off.”

A member of the audience asks about the importance of the driving scenes, to both move through the landscape and advance the story of the main character.

Ivan: “It was all there in the script and that’s why it was important to have the right car and to feel like you’re inside the car. I really wanted to feel like you were there within this car. And one of my favourite moments is when he does a sharp turn and you’ve got Charlie in the car with him and he’s holding on like that and you feel like you’re a part of it. It was always there within the script and the car was always going to be a character in the film.”

THERE IS NOTHING LIKE IT – REFLECTIONS ON FILMMAKING

A student of the Master of Arts Screen: Directing asks Ivan about reflecting on his own work and how such immersion in thought can become somewhat existential, leading to questioning the reasons for specific decisions and endeavours.

Ivan: “Maybe a year ago I was kind of going to quit and become a photographer for a while. To do photography because I kind of started in photography and I bought all this camera gear and stuff. So, if I wanted to, I could just step into that world right tomorrow. But I just think I just needed to have a rest after making this film and reassess and refocus.”

Ivan:

“I think you need that feeling of questioning. That is the perfect inspiration. It’s like when I’m writing something, you go through some bad emotion and feeling and, from experience, even though it doesn’t feel good, it’s great because you know that that is like something that’s like an egg that’s coming out and then it’s going to be great, whatever that thing is. That bad emotion is going to come out and it’s going to reveal itself in some kind of work.”

Ivan: “And after you’ve been through that process a few times, you get used to it. You just wait it out, you know, and then it’s going to come good. It’s almost like… To create something, you just got to have some really bad feelings. But the important thing is to know that it’s a process and it’s kind of a natural thing. I kind of feel like I need to be sharp as I can when it does happen, to really jump on it and to take it somewhere when it does come through. You get to the point where all of a sudden you just feel, “Holy shit, this is a filmmaking thing!”. Is like the more sensitive you get to it, the more it gives you and more it opens up and it can kind of be anything you want it to be. As long as you just be sensitive to it, and I just think it’s funny. When you first start, there’s a magic about it, right? When you’re a student and you see people shooting stuff. It’s a big deal to make a film. And there was a magic about it.”

The period of adaptation and finding one’s place and voice after the first filmmaking experiences presents its challenges, Ivan refers to it as a bubble burst, when the magic temporarily reveals the difficulties of practice, and he then reflects on how he wouldn’t want to do anything else.

Ivan:

“But now I actually find it more magical than ever because I feel more intimate with it and more engaged with it and what it can be. So, what I’m saying is that it’s such a special, special thing and I would never dream of doing anything else.”

Ivan goes on explaining how accessibility to new technology, such as the large format sensor mentioned above, makes it easier to explore as a filmmaker, and he underlies the importance of knowing who your audience is, and really tune in to it from the beginning of the creative and writing process.

Christine Kirkwood (AFTRS alumni manager), knowing that Ivan taught himself how to play the piano during his time studying at AFTRS, asked him about the music process for creating the scores for his films.

Ivan: “Like everything, is from very early on as the script is coming together and the locations and the camera and the lens and the soundscape and the music or non-music is there. So, I’m doing a horror film next and I’ve already kind of scored the bulk of it and that that is actually very influential in how I’m writing it, listening to the music that I’ve created. It just comes on early.”

Ivan and Christine reminisce about the piano and the old school location, with Ivan contemplating those formative years.

Ivan: “I had a lot of time there [at AFTRS’ previous North Ryde campus] and had a lot of time to just reflect on, you know, my future.”

Reflection and reiteration present as a fundamental part of Ivan’s process in creating stories for screen, and Limbo masterfully crafts this approach to being, by following a slow-burn character development informed by the landscape.

Thank you to Ivan Sen for being so generous with your time and knowledge, to David Balfour for hosting the event in such an insightful way and to Christine Kirkwood (Alumni Program Manager) and the Library Team for organising this wonderful evening.